Every Heart a Doorway is the kind of book you have to read to believe. The first in Seanan McGuire’s stunning Wayward Children series introduces us to Eleanor West and her strange school. Imagine a boarding school for children like Alice, who fell into Wonderland and suddenly came back into the real world, and you’re halfway there. Though the series is now a beloved fantasy staple, that wasn’t always the case. To celebrate the release of the seventh novella in the series, Where the Drowned Girls Go, we sat down to chat with McGuire about the origins of Wayward Children. She introduced each of the stories in the series for us. Put on your best adventuring gear and follow us down the rabbit hole.

The Origins of Wayward Children

Like many kids who grew up poor, McGuire found her love of stories through preloved books. Those fantastical yarns became foundational for the author and the Wayward Children. “As a child in the 1980s,” McGuire explained, “I was getting a lot of children’s fiction from the ’50s and ’60s, which included a whole bunch of things like Five Children and It, The Boxcar Children, and all of those children’s classics no one has heard of anymore, which is a bit distressing.”

It was that experience alongside the era she grew up in that sowed the seeds for what would later become Wayward Children. “While this was going on I was a child in the ’80s, which was really the resurgence of portal fantasy in at least the American consciousness. We don’t necessarily think of 1980s children’s cartoon properties as being portal fantasies. But they very much were. They were commercials and they wanted you, as the child watching, to imagine yourself having these great adventures. So you’d have the Dinosaucers or Transformers or Care Bears, depending on which side of the franchises you were on, having these grand, glorious, intensely dangerous adventures with a small kidnapped human child around to observe on it for the audience at home. And those really are by definition portal fantasies.”

She continued, “The very first My Little Pony movie starts with Firefly kidnapping Megan over the rainbow and never bringing her back. It’s a portal fantasy story. The ponies needed someone with thumbs and Megan apparently fits the bill. So portal fantasies have always been exceptionally key to me! But up until the last couple of years, they were not trendy. They’d been in the ’80s and the nostalgia wave had not swung back to them yet. Everything swings in about 20-30 year cycles. So portal fantasy stories were not a big deal.”

Bringing Wayward Children to the Page

That was the backdrop when McGuire heard from Lee Harris. The pair knew each other through Angry Robot Books. Macmillan had recently hired Harris to start an imprint: Tordotcom Publishing. McGuire recalled, “He contacted me and said, ‘You’re pretty nice and I don’t usually want to kill you with a stick. How would you like to come and write something for my new imprint?’ And I thought this was a brilliant idea and asked him how much editorial oversight would I have on the first book, and he said, ‘Pretty much none, we don’t have much money, so we’re not paying you as much as we usually would, therefore we will not tell you what to do!'”

For McGuire, it presented the opportunity that she’d been waiting for. “I said, ‘Hey, can I do a boarding school for survivors of portal fantasies?’ And he said, ‘No one is going to read that, certainly!’ So basically it was the combination of media poisoning at a very young age and being told that for once no one was going to tell me what to do.”

McGuire kindly agreed to introduce each of the series in her own words. Beware as there are some light, but McGuire approved, spoilers for some of the books.

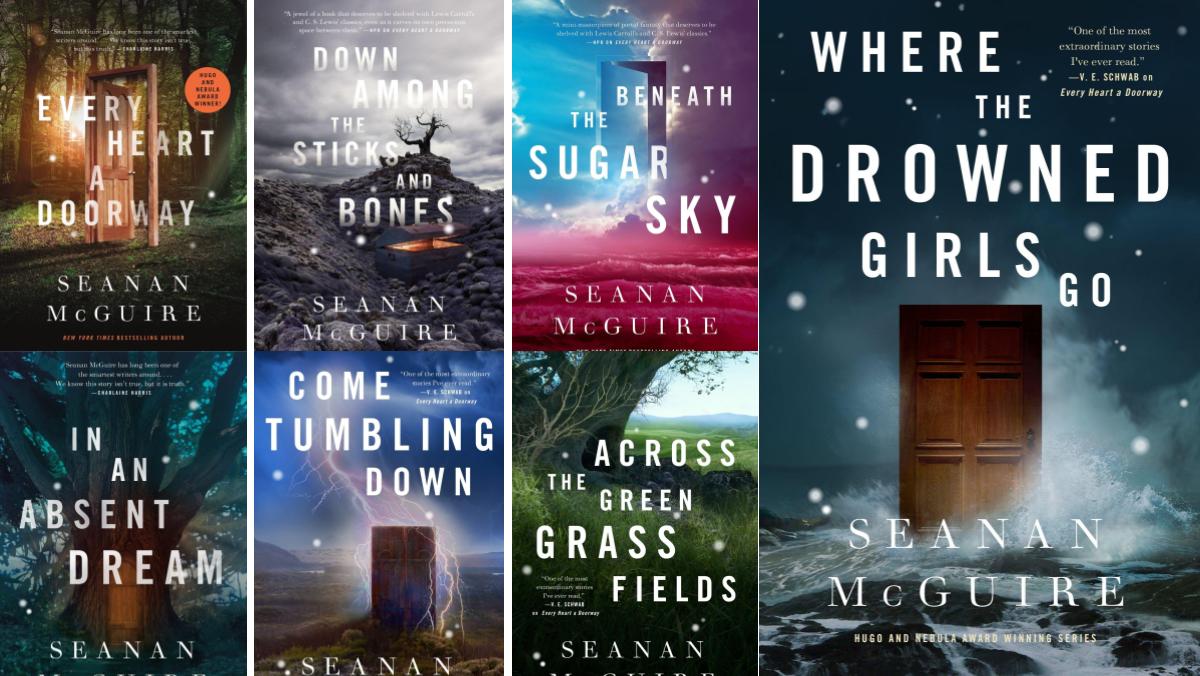

Every Heart a Doorway

“Every Heart a Doorway is very much in the tradition of the old British children’s literature boarding school books. Unfortunately, I am not comfortable referencing the most well known of those series by name. But Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children falls into that listing. The X-Men honestly are of that genre. Any story where you’re going to take people and put them in a school setting and have that as your framework, it’s part of a very well established tradition in British children’s literature, which I’ve read way too much despite being an American.”

“It’s a story about losing home and finding home and coming home. A lot of home in there. And it’s about setting up a world. The first book you do is the one that kind of sets the rules and then the second book is where you kick the tires and explain that those rules are sturdy enough to stand up to things. It’s about a girl named Nancy. It’s not a spoiler to say that literally every character we’re going to talk about today traveled through a door to another world.”

“That’s the premise of the series. These are people who went through a door that was marked in some way with the phrase ‘be sure.’ They spent some time on the other side of that door which was in some way perfect for who they were at the moment that they went through. The doors only come for you if you can truly be happy and be yourself on the other side of those doors. So Nancy went through. And then one day Nancy got dropped back into the world that she came from and it was not perfect. She had been in a place where she could finally just be Nancy and be the things that made her happy and not do any masking and not do any pretending.”

“As anyone with autism or ADHD or OCD will tell you, if we stop masking for a while—if we’re allowed to just be our natural weird gremlin selves, whatever that looks like—then putting a mask back on is 10 times more energy-wasting than having it on in the first place. Nancy lost the ability to pretend to be what everyone around her wanted and got shipped off to boarding school. So you get to meet everyone at the boarding school and then you get to see them start getting murdered. That was Every Heart a Doorway. It’s a novella at about 40,000 words long and it makes me very happy!”

Down Among the Sticks and Bones

“The closest to an autobiographical character in this series, in a lot of ways, is a girl named Jack Wolcott. Jack is short for Jacqueline and she’s the first character I have written with obsessive compulsive disorder that manifests in a way similar to my own. We meet Jack and her sister Jill in the first book, and their names are intentionally twee. I did not do that by mistake! Jack and Jill went through their magical door and in their portal world went to basically the setting of a Hammer Horror film. Like you expect Peter Cushing to step around a wall at any moment. And they spent their time in this black and white world. They got separated there. Jill wound up being the daughter of a vampire, Jack wound up working for a mad scientist. Then they got dumped back out and wound up at the school.”

“So for Down Among the Sticks and Bones I wrote the actual portal fantasy. It was so refreshing! I love writing portal fantasies; they’re ridiculous. The school books—which are the odd numbered books in the series—basically follow the rules of our world. The children can and do bring some magic back with them, but for the most part up is up and down is down, and you can’t walk through walls. You have to take math classes even if you’re the hero of a secret fantasy world that no one really believes exists. But then you go through the door and you’re in one of these portals and the rules there can be anything.”

“This is the story of how Jack and Jill went through their door and how they got kicked back out. And the thing I like best about portal world books is—again, not a spoiler—every single character is going to lose their world at the end of the book because that is the point of them.”

Beneath the Sugar Sky

“Beneath the Sugar Sky is taking advantage of several of the features I built into the world. One of the things is that the doors are not necessarily connected to one another. So you’ll go through one door and it’s a portal world like Oz, which is a little silly but again has consistent physical rules. And you go through another door and it’s a portal world like Wonderland, where nonsense runs the day. Everything is just going to do what it’s going to do and you don’t have continuity.”

“There were a lot of characters murdered in Book One. One of them had gone to a nonsense world called Confection. And then in Book Three where we’re back to the school, that character’s daughter falls out of the sky and lands in the turtle pond to the great consternation of the turtles. So it turns into a quest book to try and resurrect this specific character so that she can go back to Confection and eventually conceive her daughter, which is super fun for me and it’s very sugary.”

“It introduced a couple of my favorite characters. There’s Cora, who’s the lead character of our most recent book. And Cora was a mermaid. It shows us that you can sometimes go to worlds that you are not suited for and why people are not suited for every world. Our dead character, who I am carefully avoiding mentioning, went to Confection and it was perfection. They were so happy there, no problems, no issues at all. Cora goes to Confection, looks at the ocean made of strawberry soda, and says that’s a yeast infection waiting to happen.”

In an Absent Dream

“This was the book that hit harder than I expected it to. Most of the portal fantasies are about characters I’d murdered before you got to see more. The lead of In an Absent Dream we spent about three pages with in total. She was intended to demonstrate the doors are not always kind. Her name was Katherine Lundy. Despite being an adult in her late 40s, Katherine was physically about nine teetering on eight. And that’s because she attempted to break the rules of the portal world she traveled to and got cursed to age in reverse. She was very slowly slipping back down to her childhood with the implication being that one day she would just wink out of existence. That was her punishment for trying to exploit the goblin market and not pay fair value for the time they’d put into caring for her.”

“Katherine was a very bookish child who went through a door into a world where no one could cheat. The main rule of the market is it’s kind of the Libertarian dream but actually working. You cannot take advantage of anyone. You must pay people fair value for anything that they offer you unless it’s a genuine gift. If I have 500 My Little Ponies and you have one My Little Pony, then asking you for one pony and asking me for one pony is a different value. So you actually have to give to each according to their needs and take from each according to their available resources. And that resonated with a lot of people because we’re living in a world that loves to take advantage of us.”

“That was kind of the sad one for me, because while I love Lundy she’s not getting resurrected. We’re not resurrecting every character who dies. That would be ridiculous. So setting up a book where that happened and then following it with her is kind of a confirmation that this is someone who’s stayed dead. So people got to kind of fall in love with Lundy and then realize, ‘Oh crud cakes, she’s definitely not coming back.'”

Come Tumbling Down

“I had to fight a little bit with Come Tumbling Down. Something that we see in TV fairly frequently is that for the first season of a show they’ve managed to get greenlit and they’re going to be on the air, but no one thinks it’s going to succeed so no one cares what they do. Every Heart was a big success, which no one expected. And so when we get to Come Tumbling Down I’m like, ‘This is the book that comes next linearly, it sets up a lot of things.’ And editorial went, ‘But we just went to the Moors. Are you really sure we should be going back to the Moors right now? Maybe it’s time to go somewhere else?’ And I said, ‘No, no, it’s time.’ And they did listen to me.”

“So for Come Tumbling Down we’re actually returning to the Moors in the school timeline, which means Jack is back and has brought her fiancé along, Alexis, who delights me. There are illustrations included in the Wayward Children books. There are two characters in Wayward Children that are not chubby, they’re not chunky, they are fat girls. We’re talking American size 22 and up. Both of them, whenever they’re illustrated, are drawn as fat girls. They’re not Hollywood fat; they’re not size 12, they’re size 22. And Alexis is one of them. And as far as Jack is concerned, she’s the most beautiful woman in the world. She’s perfect. And I got to spend some time with Alexis, which was nice.”

“Come Tumbling Down is very much a quest book. It’s an attempt to right a wrong that’s threatening to unsettle the balance of the Moors in an absolutely terrible way that they probably wouldn’t have recovered from. We get to spend time with some of my favorite of the Wayward Children. We get to hang out with Kade a bunch. He delights me, he’s very practical! ‘Why do we have to be here right now? Why is this happening?'”

Across the Grass Green Fields

“Across the Green Grass Fields is a good example of my policy on representation. I have a good friend who’s intersex. The first time we met we were talking about My Little Pony, as we’re both big Generation One My Little Pony fans. Then they went and did panel, and on that panel someone said, ‘If you have an intersex condition and do not disclose it on the first date, that’s a consent violation.’ In my opinion I don’t think there are any consent violations involving my body and when I tell you about it unless I’ve given you permission to have sex with it. And I’m not normally doing that on the first date. So they were talking about how they never get to see characters with intersex conditions in fiction, or if they do it’s in the after school special type.”

“So Across the Green Grass Fields is basically a love letter to Generation One My Little Pony. Regan, our main character, has the same intersex condition that my friend has. Regan has an intersex condition and it doesn’t harm her. It’s not impacting her quality of life. But it does cause some commotion at school when she mistakenly reveals this fact to someone she thinks is a friend and gets treated very poorly accordingly. So she runs away and she winds up in the Hooflands, which is a place where everything has hoofs and she has a bunch of adventures there. And at the end of it she’s back in this world.”

“Across the Green Grass Fields was the first Wayward Children book we’ve had where we have the portal fantasy before we have the child. And that’s really important because in the newest book we really start to see the effects of continuity.”

Where the Drowned Girls Go

“Every Heart a Doorway was easy in some ways because I could just be like, ‘Oh, there’s this kid.’ There’s no preconceptions, no one has any ideas about who they are. But by this point in the series, especially for the school timeline books, you know who Sumi is, you know who Kade is, you know who Christopher is, and you have opinions about them.”

“So Where the Drowned Girls Go is very focused on Cora, our mermaid. She’s dealing with PTSD from her experiences in the Moors during Come Tumbling Down. And she decides that the way to deal with it is to just forget that she’s a mermaid. She’s going to reject her trauma and reject the fact that it happened by convincing herself that the doors aren’t real and therefore it couldn’t have happened. And part of how she does this is by switching her enrollment from Eleanor West’s School for Wayward Children to the Whitethorn Institute, which is a school explicitly for helping kids forget about the doors.”

“Whitethorn is very much set up like the scary Gothic boarding schools that we see in a lot of horror movies. But it’s also like the gay conversion camps in many places where it’s absolutely legal, especially for the parents of queer teens who have very little autonomy, to grab them in the middle of the night and throw them in a camp that’s going to teach them not to be gay. Really, I find that those camps mostly teach kids not to be alive. So I knew Whitethorn would be a traumatic setting for many people. It’s a traumatic setting for me, but it was important we finally got there.”

“So we’re following Cora as she begins to understand that denying you were hurt is not the way to heal. She’s grappling with her trauma and finding some ways of recovering from her trauma. She’s not healed at the end of the book, that’s not how trauma works. But she’s in a better position to take care of Cora and to stop hurting herself to help the people that hurt her in the first place. It was also really convenient because it let me introduce like half a dozen new characters, because when you murder people as often as I do you run out!”