What happens when you censor murderous art? Well, more murder, apparently. At least, that’s what happens in the third episode of American Horror Stories. The episode “Drive-In” raised a few curious eyebrows when it was revealed that Tipper Gore (played by Amy Grabow), the former Second Lady of the United States (1993-2001) and wife of Al Gore, would be a part of this fictional tale. She doesn’t make a lengthy appearance in the story, nor does she get in deadly harm’s way. But her inclusion and role in this saga about art and censorship makes a ton of sense when you look at her real life opposition of questionable content.

Alright, this is where things get spoilery, so reader beware. This story’s antagonist is Larry Bitterman, who lives up to his last name on several occasions. His film, Rabbit Rabbit, is a wash of disturbing images, noise, and screaming with presumably no plot (at least, from what I heard). The flick makes unsuspecting audiences turn into flesh-consuming zombies. And not the slow ones like The Walking Dead. It’s the snarling, running jokers from 28 Days Later.

FX/Hulu

A modern day group of kids, including the male protagonist Chad, talk about Rabbit Rabbit’s history. Specifically its 1986 banning after one showing. Why was it banned? Because six people died in a massacre at the theater that night. The film’s horrific show led to it becoming a mythical cursed legend among horror geeks. Of course, Rabbit Rabbit is now coming to a drive-in movie near the kids and they must go see it.

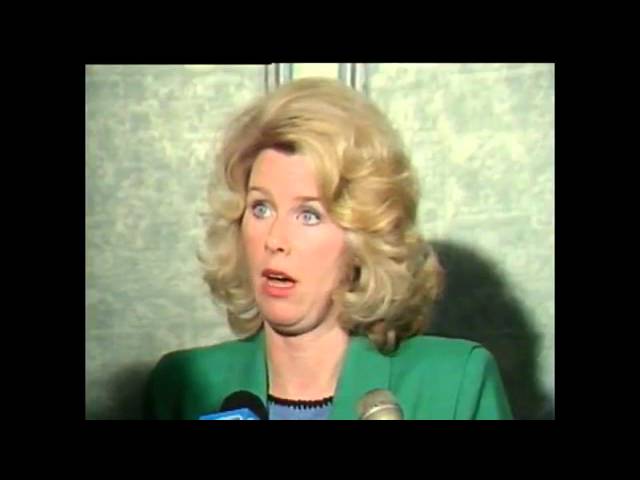

Chad does some investigating and discovers a CSPAN video of Tipper Gore giving Bitterman the business at a congressional hearing. She has come up with ample evidence that he made it to incite violence on purpose. And she’s also taken the liberty of making sure the distributing studio cancels the film and destroys every copy. Bitterman isn’t happy about this, so he lunges over tables (because what is security?), assaults her, and lands in prison for 15 years. This is a fictional account, but an interesting snapshot of Tipper Gore’s history with censorship.

In 1985, Gore founded the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) with several other political wives. The group’s aim was to increase consumer awareness of music with explicit lyrics and/or suggestive content. They came up with a list of 15 songs that were “objectionable” because of sex and/or violence in the lyrics, which became known as the “Filthy Fifteen.” The list includes artists like Madonna, Mary Jane Girls, and AC/DC, among others.

Tipper Gore came up with this idea after hearing her daughter Karenna (then 11) listening to “Darling Nikki” by Prince. She took her demands for the now-infamous Parental Advisory stickers and warnings about content to a Senate panel that year. The sticker came around during the hearing in November 1985 and still exists today.

From her perspective, Gore didn’t want to control artists creative freedom. She said it would help parents have more regulation over what their kids could access and listen to. Needless to say, her endeavor didn’t fare well with rock and hip-hop artists. Their fanbases had a fair share of tween and teens. (Remember, these are the olden days when people bought albums and stuff.)

FX/Hulu

Musicians like Joey Ramone and Dee Snider said Gore and the PMRC were censoring their music. Some artists took shots at Gore and PMRC through their music. (In is song “Freedom of Speech,” Ice-T referred to the group as “stupid a**holes.”) As we all know, artists have continued making suggestive material. And for ‘80s and ‘90s kids, that infamous Parental Advisory sticker made us only want to get our hands on an album even more.

To further put things into context, all of this takes place at the height of Satanic Panic during the 1980s and early 1990s. During this time, many parents were already paranoid after the 1970s introduced a rise of murders centering around satanic/odd rituals like the Zodiac Killer and films like The Exorcist. Heavy metal and Ouija boards became works of the devil. So there was a fair share of paranoia which, of course, only made rebellious teenagers gravitate towards “forbidden fruit” more.

So, it totally makes sense that Tipper Gore would not be happy about a film like Rabbit Rabbit. It didn’t just allude to but actually led to horrific violence, after all. “Six people are dead, killed watching your movie,” fictional Tipper Gore says to Bitterman. “We’re [the PMRC] Americans, concerned about the effect of violent content on our society…so you think all of this attention will just increase your audience?”

Rabbit Rabbit plays despite the warnings of a great doomsayer, who was at the original showing. Pretty much everyone in attendance goes full zombie and dies. The exceptions are Chad and his girlfriend Kelley, who don’t watch the movie because they are having sex. (Yay for subverting the “you have sex, you die” trope!) They hunt down Bitterman, who is thrilled that his film led to mass murder. Horror inspiring horror, I suppose. Bitterman reveals every detail of his history and current plans to make the world pay for “censoring his art.”

He was a second assistant cutter for The Exorcist and responsible for the subliminal messages that shook audiences. Bitterman’s anger over not winning Best Picture led him to deeply study subliminal messages and things like Project MKUltra to make Rabbit Rabbit. The flick made audiences snap in 1986 and the subsequent intrigue gave him joy. But Tipper Gore didn’t allow his momentum to prosper. He reflects on his censoring and prison time, telling Chad and Kelley that “a society that locks up its artists doesn’t deserve to survive, it deserves to burn.”

Bitterman spends his prison time fixing and refining his film. He gets out and made a new, infinitely worse cut that kills everyone. In the end, he does win even in death, as evidenced by his Rolls Royce and Rabbit Rabbit’s distribution deal with Netflix. We doubt that Tipper Gore will watch it but she probably won’t be able to stop the violence this time around.

“Drive-In” left a load of questions that won’t get answers. And there are certainly some eyebrow raising decisions made in it. But including Tipper Gore, even if only for a couple of quick flashbacks, is a small yet brilliant move to establish how a person’s sensitivity about their art can become a real-life horror story.