Most dog owners out there know their pups are stellar at picking up cues—even very subtle ones. (Especially when it comes to anything having to do with the kitchen.) But a new study from researchers in Hungary shows that dogs are so adept at detecting changes in human behavior they even know when we’re speaking a different language. Hopefully their spelling still isn’t great though because they get too excited when it’s time for a W-A-L-K.

Gizmodo picked up on the new study, which researchers recently published in the journal NeuroImage. The researchers note in their study that “the extent of [dogs’] abilities in speech perception is unknown,” and that this study was, in essence, a way to test speech detection and language representation in the canine brain.

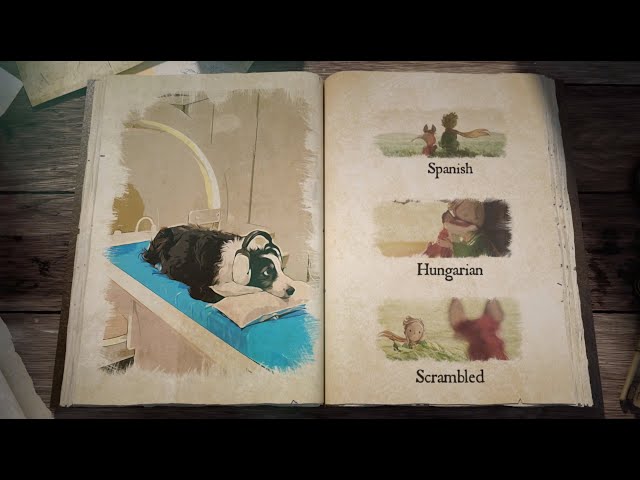

To explore the way dogs process language the researchers collected 18 dogs capable of holding still in an fMRI—or functional magnetic resonance imagining—machine for long enough to have their brains scanned. The researchers then had the dogs listen to natural speech and scrambled speech in both languages familiar and unfamiliar. Specifically, the researchers read The Little Prince in Hungarian speech for dogs familiar with Spanish-speaking owners. And in Spanish for dogs familiar with Hungarian-speaking owners.

As the lovely little video below describes, the researchers hit upon two findings. The first: no matter which language dogs hear, they’re able to distinguish speech from non-speech. Something they do in their primary auditory cortex. The second: via their secondary auditory cortex, dogs are able to distinguish between one language and another.

“We found that they know more than I expected about human language,” Laura Cuaya, a postdoctoral researcher at the Neuroethology of Communication Lab at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary and lead researcher of the study, told NBC. Cuaya, who included her dog Kun-kun in the study, added that “Certainly, this ability to be constant social learners gives them an advantage as a species — it gives them a better understanding of their environment.”

The researchers say this is the first time anybody’s found evidence of a non-human brain distinguishing between languages. Although it’s still a mystery as to how the canine brain evolved over thousands of years to develop this capacity. Likewise, it’s not exactly clear why older dogs, and dogs with longer snouts, were better at differentiating. Which sounds like a good enough reason for Cuaya and Kun-kun to sniff out some more grant money.