The history of the controversial Black Panther Party largely focuses on its male members. There are many classic photos of proud Black men wearing all black; they don leather jackets and berets while throwing up a Black Power fist or wielding guns. Films like Panther and, most recently, Judas and the Black Messiah focus on prominent men like Fred Hampton, Huey P. Newton, and Mark Clark; however, there were key women figures in the organization as well. The story of Elaine Brown, the Black Panther Party’s only chairwoman, is worthy of acknowledgement and celebration.

Early Beginnings

Elaine Brown grew up on the cusp of poverty and privilege as a North Philadelphia girl attending predominately white schools. After a brief stint at Temple University, Brown chased her songwriting dreams to Los Angeles; its where she first became involved in the burgeoning Black Power collective. In the mid to late 1960s, Black people’s desire for safety and self-sufficiency along with a demand for more direct physical action vs. non-violence/peaceful protest led to this pivotal movement. The assassination of Malcolm X, riots, and America’s socioeconomic injustices further bolstered the desire to not “turn the other cheek.”

Organizations focusing on Black nationalism like the Black Panther Party became a source of power and pride for Black people. It was during this time when Brown’s interest in politics and social justice grew through her work with the radical newspaper Harambee. Less than a month after her 25th birthday, the Civil Rights movement (and world) changed with Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April 1968.

Elaine Brown went to her first Black Panther Party meeting that same month, soon joining the relatively new organization in Oakland. Students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party in Oakland, CA in 1966; it quickly gained steam among Black young adults. The Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Program spelled out their desires. Freedom, employment, decent housing, comprehensive education, military exemption, and an end of police brutality and murder among other things.

This puts the timeline between her joining and the events of Judas and the Black Messiah into the same era; however, those events took place in two different American cities. Brown did know Hampton to some extent but she was not a prominent member of the organization during his life.

The group pushed for Black liberation and empowerment, but it seemed this mainly had Black men in mind. In the organization’s early days, women did more “menial” tasks like selling newspapers, cleaning guns, and other assistant type of work. The Black Panther Party’s ideals were built on a patriarchal foundation so members didn’t want a woman to be assertive or attempt to obtain leadership. A woman’s job was to stand behind the Black man and be his support.

Party Contributions and Rise to Leadership

Brown helped with the Party’s many beneficial community programs like Free Breakfast for Children and its first Free Busing to Prisons and Free Legal Aid programs. She soon became the editor of the Black Panther Party’s Southern California Branch publication along with releasing her album Seize the Time. The latter gave Black people’s plights in America a soundtrack despite being about several key Party members.

“The Meeting, ” a dedication to Eldridge Cleaver, became the Party’s anthem at the behest of Chief of Staff David Hillard. Seize the Time didn’t make any commercial waves because Brown did not have a “Black sound,” but its lyrics are all about Black pride and power. She began to climb the ranks in the organization, becoming a part of the Central Committee as the Minister of Information (replacing Cleaver) in 1971.

By this time, the Party’s official stance on women began to change with newspapers and some leaders condemning sexism. Many Black Panther Party leaders, including Hampton, died due to the group’s perceived militancy while others went to prison for different reasons; this left a chasm for women to fill as their numbers grew within the organization.

Brown began to work with Newton, who encouraged her unsuccessful runs for Oakland city council in 1973 and 1975. However, her life went through a major shift in 1974 when Newton fled to Cuba to avoid criminal charges. He appointed her to lead the Black Panther Party as its chairwoman. She occupied that position for three years, focusing on electoral politics and community service and cultivating a Black Panther Liberation School.

Despite some pushes towards gender equality, there were still men who didn’t want to take orders from a woman. Brown documents her experience with BPP leadership and sexism in her 1992 memoir A Taste of Power: The Story of a Black Woman:

“A woman in the Black Power movement was considered, at best. Irrelevant. A woman asserting herself was a pariah. If a Black woman assumed a role of leadership, she was sad to be eroding Black manhood, to be hindering the progress of the Black race. Shew as an enemy of the Black people…”

Nevertheless, she began to appoint women into key administrative and leadership roles as their numbers kept rising. Women like Angela Davis and Ericka Huggins also became powerful women in the movement. This sense of equality was refreshing for some members but, for others, it challenged their long-held notions about what it meant to be oppressed and gender norms.

They were unable to see the intersectional issues of sexism and racism for Black women, instead believing that racism was more oppressive than sexism. For Brown, her experience with sexism came to a head in 1977 after Newton returned from Cuba. He came back to complaints from some men about women overpowering the organization. According to Brown, male members of the Party beat Regina Davis, a Panther Liberation school administrator, for reprimanding a male coworker. Newton stood with the men, causing Brown to leave the Party and return back to Los Angeles with her young daughter Ericka. The Black Panther Party subsequently began to dwindle in numbers, with most programs and schools closing by 1980.

Her story is a glaring reminder of the issues that Black women in America face. Outside of our communities, our gender and race lead to a double whammy of oppression. We earn less than men and our white female counterparts regardless of education background. We have to carefully navigate public places to avoid the “ angry Black woman” or “difficult” labels. There is judgment about our family planning decisions and whether we fall into certain patriarchal norms.

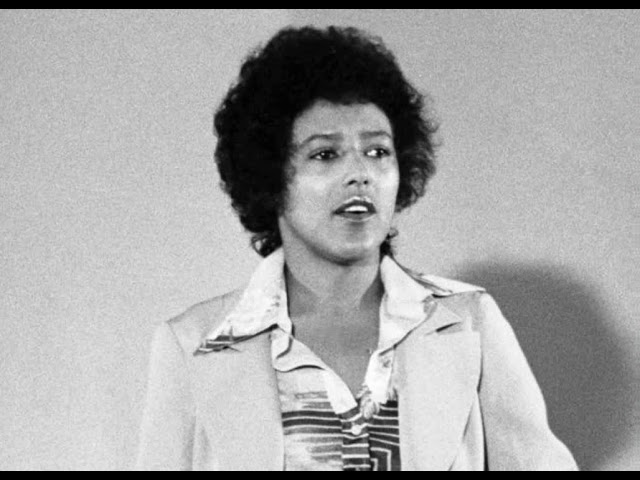

AfroMarxist/YouTube

Black women are expected to “save” and stand for everyone; however, when we get too loud or bold, there’s someone looking to take us off the pedestal. Sometimes that person is white and other times it’s a Black man who wants to keep us “in our place.” Sadly, some Black men are willing to put their figurative foots in our backs while grasping their male privilege to get a leg up in the world. They can clearly see the effects of racism but cannot understand how sexism is a part of this harmful framework.

Mistreatment by others is difficult but a betrayal by our own men whom we often support is painful. Elaine Brown’s feelings of betrayal and disappointment are relatable to virtually every vocal Black woman. Thankfully, her story is so much bigger than her time with the Black Panther Party.

Post-Party Programs and Presidential Musings

She went to law school in the early 1980s and eventually moved to France in the early ’90s. Brown came back to America in 1996, settling in Atlanta and quickly getting to work in the community. She founded Fields of Flowers, Inc., a non-profit organization aiming to help Black children in poverty. Brown’s passion for helping children was also the cornerstone of her work through Mothers Advocating Juvenile Justice; she co-founded the organization to advocate for incarcerated youth, specifically those being tried as adults in Georgia.

Her 2002 nonfiction book The Condemnation of Little B examines the real-life case of Michael Lewis, who received a life sentence at 14 years old for a murder she believed he did not commit. The book uses his case to talk about the larger issue of Black children receiving lengthy or life sentences. In addition to helping youth, Brown also co-founded the National Alliance for Radical Prison Reform. Its aim is to assist people with finding housing/employment post-incarceration and transportation for family prison visits. This is in addition to an urban farm initiative to give jobs to formerly incarcerated people.

In 2007, Elaine Brown became a presidential nominee for the Green Party. Her platform focused on providing livable wages, free health care, public education funding, affordable housing, and environmental improvement. Unfortunately, she resigned later that year because the Green Party was dominated by, in her words, “whites who had not intention of using the ballot to actualize real social progress.”

Brown spoke to The Washington Post in 2018—50 years after she joined the Black Panther Party. She said she continues to work for social justice and criminal system reforms. Elaine Brown may not be a household name, but she certainly made history. She took the helm of a controversial organization and instilled her desire for liberation of Black people into its programs. And, years later, she is still saying, “All power to the people!” and speaking across the country about the ongoing fight for Black liberation.