Some film genres are not appealing to certain cinephiles. Some people say “no way” to straight-up horror while others aren’t keen on romantic adventures. However, the one genre that the majority can watch and find entertainment and value within its narratives (at least, to some degree) is action. There’s truly something for everyone under that umbrella, whether it’s an epic sci-fi space saga, spy fiction, or a shoot ‘em up style story. From tried-and-true flicks like Die Hard to newer classics like the John Wick franchise, action movies have been a major part of our entertainment experience for decades. But where did it all begin? What is the first movie that set the action genre in motion? Let’s get into a bit of film history.

As always, it is hard to pinpoint a “first” in decades past considering the plethora of independent creatives whose works may not be on our general radar. But quite a few film historians generally agree that the first action movie ever is The Great Train Robbery, directed by Edwin S. Porter, who also did the film’s cinematography.

The Great Train Robbery’s Daring Plot

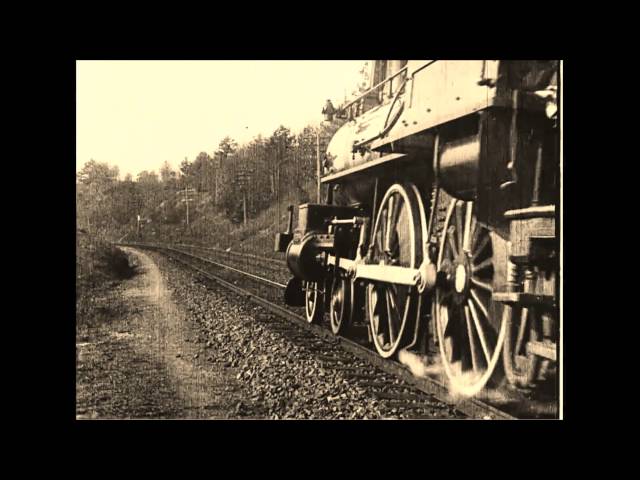

The Great Train Robbery is a 1903 black-and-white silent film. It’s loosely based on the 1893 stage play of the same name by Scott Marble. (We will dig into its history and conception story later.) The 12(ish)-minute flick follows a band of outlaws who rob a steam locomotive station, flee across the mountains, and eventually face defeat at the hands of a crew of ambitious locals. The Great Train Robbery wastes no time jumping into action. It starts with a robbery at gunpoint before the bandits take over a moving train. They commit murder, accost the conductor, and force all the passengers off the train after looting them before heading back towards a valley.

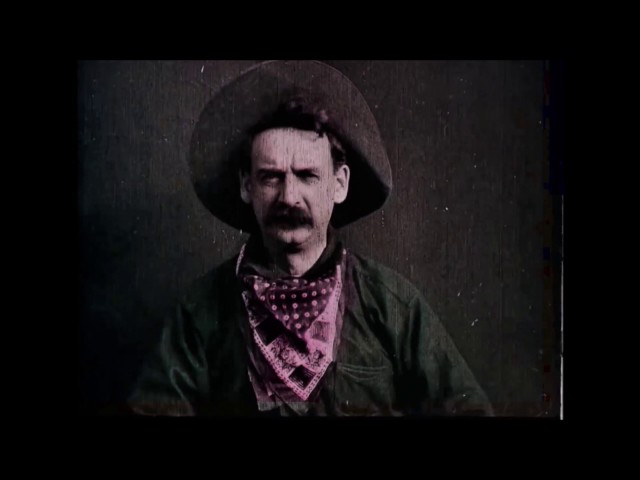

The vagabonds meet their match thanks to a band of heroic guys who save the day. The film ends with one bandit emptying his pistol into the camera. This chilling final frame was primed to become pop culture history. During this time period, The Great Train Robbery was quite the rousing spectacle with its action, violence, suspense, some serious piano playing, and solid practical effects for a film of this era. Even with an actual plot, does it still slightly lean more towards visual spectacle than character development and tightening narrative gaps? Yeah. However, imagination and personal interpretation can fill in those spaces and create a unique experience.

The Great Train Robbery’s History, Inspirations, and Filming

The early-1900s film landscape was a time of great innovation and chaos as everyone wanted to get their slice of the moving picture pie. Prior to The Great Train Robbery, Edwin S. Porter started his career making film equipment like cameras and film projectors. He notably created a device to regulate the intensity of an electric light, which changed the game for future cinematographers. After a fire destroyed his workshop at the turn of the century, Porter took a contract project with the Edison Manufacturing Company to improve their equipment.

The venture was successful and Porter became a cameraman. At the time, a movie’s cameraman also had creative control akin to what directors have today. This made it a powerful behind-the-scenes position. Initially, Porter’s style was simple and straightforward to mimic the signature approach of the Edison Manufacturing Company. But, he began to branch out and explore foreign films. This happened around the same time that George Méliès set the industry on fire with the first sci-film film, A Trip to the Moon (1902). Scammers and pirates (including known messy man Thomas Edison) imitated his style and hit his pockets hard.

A Trip to the Moon‘s multiple scenes, meticulous editing, and special effects encouraged Porter to bring that sort of energy into his work. Unfortunately, Edison later distributed illegal copies of Méliès’ film, contributing to the rampant industry issue of securing copyright. (As a note, Porter later made the very questionable Uncle Tom’s Cabin. That earns him a side eye on general principle.)

Meanwhile, Porter delivered movies like 1902’s Jack and the Beanstalk, which was obviously influenced by Méliès style, and Life of an American the following year. The latter is where he began to use a novel editing technique called dramatic editing. Scenes shot at different places and times were pieced together. After some success, he set his sights on The Great Train Robbery. The film was inspired not only by the aforementioned play of the same name but also Westerns. Even then, people loved a good story happening in the open lands of America.

So, to be clear, The Great Train Robbery is far from the first Western film. However, it was certainly an early influence for the TV and films that would follow. Stage Coach Hold Up and the British film Kidnapping by Indians were likely direct influences on Porter’s work. And, of course, art always has a way of imitating and reflecting its time period. In 1900, Butch Cassidy and his comrades robbed a Union Pacific Road train and escaped capture. What better content to further fuel your narrative?! Combined with the public’s general affinity for trains and desire for entertainment, this film was ready to move full steam ahead.

Filming took place over a few days in November 1903 (only one month before its official release!) in several locations, including the Edison studio in New York and along the now-defunct Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. The railroad spanned from Buffalo, NY to Hoboken, NJ so not exactly the West, but good enough. The cast included Justus D. Barnes as the leader of the outlaw collective, Walter Cameron as a sheriff, and G.M. Anderson in several roles, including a murdered passenger and a robber. To save a little cash, several Edison employees took on background roles. No major stars like Tom Cruise and Denzel Washington were around at the time to lead the way. But Anderson later became a legend who is known as “The First Cowboy-Western Movie Star.”

From a filming standpoint, The Great Train Robbery’s outdoor locations, combination of studio scenes with onsite footage, and several shots with a moving camera gave it an edge. All of this fed into Porter’s primary aim to focus on action and style versus character development.

The Great Train Robbery’s Release, Reactions, and Enduring Legacy

The Edison Manufacturing Company began to tease the film to exhibitors in November, saying it would be a sensation. A rough cut of the film also went to the Library of Congress in order to secure a copyright on its material. Edison sold the final cut to exhibitors to screen in vaudeville houses for $111, with the first showing taking place at Huber’s Museum in New York City. It became a success as the headlining attraction at several vaudeville houses before making its way to new entertainment venues like nickelodeons, indoor exhibition spaces designed to show motion pictures for, you guessed it, a nickel.

The Great Train Robbery was a hit among audiences and some early film reviewers/critics praised its action scenes and timely material. Despite submitting the film to the Library of Congress, a few imitators still had their own versions. The most egregious one comes from Lubin Manufacturing Company in 1904. This remake of sorts, hilariously named The Bold Bank Robbery, changes some basic plot details, but it is hard to deny that the story remains awfully similar.

Back then, the parameters around film copyright were still nebulous. And, to be honest, it was a bit of Edison getting a taste of his own medicine. In 1905, Porter hilariously made fun of his own film with The Little Train Robbery. The story follows kid bandits stealing candy and toys.

Decades later, The Great Train Robbery continues to resonate with film historians and fans of action films. Several cornerstone elements in Western (and general action) films like fisticuffs, gunplay, and riding on horseback to pursue a target. In fact, we saw all three of these in the recently released John Wick: Chapter 4. In 1990, The Great Train Robbery was added to the US National Film Registry for its significance in popular culture.

The final close-up scene of Barnes staring at the camera is undoubtedly the film’s most influential and iconic shot. It doesn’t tie into the narrative in any way while also breaking the fourth wall. The shot can be seen as a message to viewers that no matter what, the violence will continue with new faces and situations. The final scene of Goodfellas when Tommy DeVito shoots at the camera pays direct homage to this shot. James Bond’s iconic gun barrel sequences also seem like more of a nod to this concept. Breaking Bad also famously ends its season five episode “Dead Fright” with an in-the-camera gunshot scene.

As they say, the rest is history. The Great Train Robbery paved the way for countless films to come that focus on intense action, hand-to-hand combat, chase scenes, and the everyday person’s capacity to become heroic.