Clarice Starling sits opposite a therapist, their session recounting a series of events familiar to fans of The Silence of the Lambs. It’s been a year since since the FBI trainee—now a graduate of the academy—discovered and killed serial killer Buffalo Bill. But he lingers still, impressed on her subconscious like a fossil of the death’s-head moths he placed in his victim’s throats. A symbol of metamorphosis for him, preserved in fever-dream flashes for her.

“I thought it was done,” Clarice says in her West Virginia twang. Subtle notes of Q Lazzarus’ “Goodbye Horses” play over memories of Bill hunched over his sewing machine, stitching human flesh. The song was a standout moment in the 1991 film, but here it’s a shadow. Because this isn’t Buffalo Bill’s story. Or Hannibal Lecter’s. It’s Clarice’s, and it fits a little uncomfortably.

CBS All Access

CBS All Access

Clarice, the new CBS All Access (soon to be Paramount+) series plants us firmly in Clarice’s world. And it isn’t exactly a cakewalk. Following her impressive detective work on the the Buffalo Bill case, she became something of a celebrity. A fixture of the tabloids. The poster child of the FBI. But it’s the 1990s. That a woman—not even an agent at the time of Bill’s killing—solved a case her male elders could not has ruffled some feathers. Couple that with the PTSD caused by her showdown in Bill’s basement, and her manipulation by the imprisoned cannibalistic psychiatrist Hannibal Lecter, and we’re left with a Clarice frozen in amber.

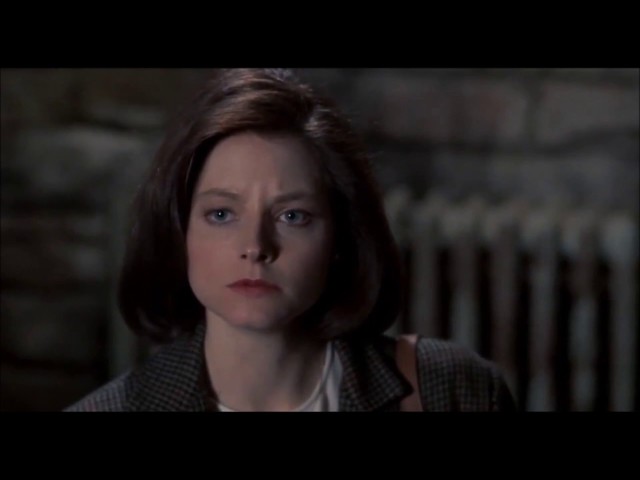

She spends her days in the basement of the Behavioral Science Lab at FBI headquarters, feeding paper to machines. She isn’t in the field tracking down killers as one might expect. She’s in limbo, and in no hurry to seek resolve. So she keeps her therapist at a distance, cracking jokes to ward off inquisition. It’s a little frustrating to see a character so resolute in The Silence of the Lambs plopped into a fairly by-the-numbers CBS procedural. But it also feels appropriate. And totally in keeping with the character made famous by Jodie Foster back in 1991, and whom Thomas Harris first brought to life in his 1988 novel.

Orion Pictures

Orion Pictures

The history of Clarice Starling

Clarice has been in the shadows for too long. Not that she isn’t beloved or respected. But she’s rarely the focal point of new Harris adaptations. It’s true that Hannibal Lecter—the flesh-hungry villain played by the likes of Brian Cox, Anthony Hopkins, and Mads Mikkelsen—came first. Harris introduced Hannibal in his 1981 novel Red Dragon, set after the events of his capture by FBI profiler Will Graham. In that book, Lecter helps Graham capture another killer known as “The Tooth Fairy.” Red Dragon has been adapted three times: as Michael Mann’s Manhunter in 1986, as Brett Ratner’s Red Dragon in 2002, and in the third season of Bryan Fuller’s NBC series Hannibal. It’s an excellent book and Lecter is the most delicious of villains—unknowable, cunning, manipulative. But his story often overshadows Harris’ secret ingredient, Clarice Starling.

Manhunter received mixed reviews and poor box office receipts upon release. But The Silence of the Lambs, released five years later, was a smash hit in every possible way. The film made $272 million at the box office off a $19 million budget. It’s also the third film in history to win the top five categories at the Academy Awards (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay) and is the first—and only—horror movie to earn the top honor. There are a lot of reasons for this. Jonathan Demme’s haunting direction, Hopkin’s disorienting depiction of Lecter, and a whip-smart screenplay that perfectly captures the thrills of the source material.

But it’s Jodie Foster as Clarice Starling that elevates everything. She’s steely and professional, but emotional, too. She’s the Clarice of Harris’ book, but also her own concoction; her small physicality not a detriment so much as a weapon. We see her flanked by male peers who loom over her in the elevator. Her womanhood is an asset in so many ways, but not in the way men like Section Chief Jack Crawford expect. He assigns her to interview Lecter, hoping her femininity disarms him. But really, Clarice’s super power is her vulnerability. She looks at the body of a dead woman and notices her nail polish; and therefore, the person she was. Insights like these lead her to Buffalo Bill. Her empathy also shields her from Lecter’s venom; even her prized cow colleague Will Graham couldn’t manage that.

Harris famously lost the plot when it comes to Clarice Starling. In his 1999 sequel novel Hannibal, she’s enmeshed in a narrative involving a pedophilic serial killer named Mason Verger, himself a victim of Lecter. Now a seasoned FBI agent, she wrestles with her place in the system and her complicated remorse for Lecter. When the cannibal psychiatrist, who’s living freely in Florence, saves her from Verger, things get really weird. Lecter feeds Clarice drugs and psychologically abuses her. But when she comes to, instead of feeling mortified, she falls in love with him. Yes, Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter become lovers on the run in Italy. It’s as grimy and upsetting as it sounds.

CBS All Access

CBS All Access

What Clarice gets right

For longtime fans of Starling, Hannibal the novel is a hard pill to swallow. It soured many of us from the source material. That is, until Bryan Fuller’s Hannibal reclaimed the name in a dazzling way. That NBC show is phenomenal and unique, blending elements of Harris’s novels into a baroque remix that centers mostly on the relationship between Lecter and Graham. For complicated rights reasons, most Silence of the Lambs characters were kept out of the series—including Clarice Starling. For those same rights reasons, the name Hannibal Lecter is forbidden in CBS’s Clarice.

But this isn’t as bad as it seems. Yes, Lecter is a central figure in Clarice Starling’s story. But that’s not always a good thing, as evidenced by Hannibal. She is just as interesting and vital without him—if a little less flashy. The lack of flashiness might detract some viewers. The show lives in the shadow of Fuller’s creation, and that’s quite understandable. But Hannibal the show existed in the headspace of male fantasy, where violence is an expression. In Clarice, violence is dull and grey. Because that’s how it is for women; unrelenting and everywhere.

Australian actress Rachel Breeds plays Starling in Clarice. She’s no Jodie Foster—because no one else is—but she finds the character’s humanity in other ways. She’s a more playful Clarice, and a more developed one, by virtue of the television format. She lives off ramen noodles and soda and Twizzlers, but works out like a maniac. We see more of her personal life, including her relationships with women. She cohabitates with friend and colleague Ardelia Mapp (Devyn A. Tyler). Wrestles with the trauma she shares with surviving Bill victim Catherine Martin (Marnee Carpenter). Tries to appease Catherine’s mother, US Senator Ruth Martin (Jayne Atkinson). All the while figuring out her place in a department that regards her skills with suspicion.

The first three episodes of Clarice are a mixed bag. It’s a CBS procedural, after all, so it must be considered on those terms. Hannibal got away with things most network series cannot, including a surprising leniency when it comes to gore. Clarice is more standard and formulaic, and has some clunky lines of dialogue and plot conventions. But it’s also highly watchable and, at its core, quite interesting. Perhaps that’s due to Jenny Lumet’s involvement. The executive producer wrote the script for Rachel Getting Married, one of Silence of the Lambs director Jonathan Demme’s last films. There’s some shared DNA in the soul of these projects; the desire to trap us in Clarice Starling’s worldview, as uncomfortable and occasionally mundane as it is.

It’s too early to say how successful Clarice will be in this endeavor, but for the first time in a long time, it feels like a project is committed to what makes her special. Not the violent men who suck up the attention. Who kill and maim and torture. But in the way women pick up the pieces they leave behind. Clean up the mess. And occasionally break down and cry when it gets to be too much. That vulnerable quality has always been Clarice Starling’s great strength, and it’s exciting to see it explored instead of silenced.